I opened my law office in the upstairs bedroom of my house on October 1, 1996, 25 years ago this Fall. It’s been a quarter century of practicing law in the digital accessibility space.

And a quarter century of practicing law with what I now call dolphin skills (thus the image of jumping dolphins illustrating this post and in my website header). I learned long ago that just because you are a lawyer, you don’t have to be a shark to get things done. More about the dolphins on LFLegal.

Over the coming months I’ll share reflections on two and a half decades of being a lawyer at the intersection of disability, technology, and civil rights. And I’ll share stories of lawyering with Structured Negotiation — a client-centered practice that fosters collaboration over conflict, relationship-building over run-away costs.

Today I’ll start at the beginning:

Why the home office?

When I graduated law school in 1981 my one and only goal was to be a union-side labor lawyer. I achieved that goal, but five years later I wanted something different. I became a civil rights lawyer handling race and gender discrimination cases in a small Bay area firm. Alas, my expectation that I would retire from that firm was cut short.

The day before I was set to become a partner, the firm’s principal owner came to me and said “You will never be a partner here. You lack grace and equanimity.” (More in my book about those two words and their impact on my path to Structured Negotiation.)

Looking back, it was pure sexism. (Actually, that was what I thought then.) But like many things, when one door shut (was slammed in my face) life opened a window. I took a four-month position at the Disability Rights Education & Defense Fund (DREDF). Four months that changed the course of my career and my life.

The four months turned into four years. Four years that gave me a foundation in disability rights and my first introduction to blind people and the need for accessibility.

One of my earliest memories? Riding the San Francisco Muni system with blind activist and marathon runner Harry Cordellos. We were working on a case whose goal it was to get city bus drivers to announce bus stops out loud. (Yes – before technology did that.)

I was just learning about what it means to be blind and Harry startled me: “Lainey,” he said,

Blind people are not sighted people with paper bags over their heads. That’s not what it’s about.Harry Cordellos, Lainey’s first blind client

In addition to working on stop-calling, those four years, from 1992 – 1996, gave me my first taste of accessible technology (Talking ATMs) and my early introduction to blind activism and the civil rights of blind people.

But as much as I loved the work, being litigation director for a national non-profit was just too much. One day I woke up with a deep knowledge that I needed a change. My daughters were 10 and 7 and I just couldn’t figure out how to be both the mother and lawyer I wanted to be in the job I had.

I had been a lawyer for 15 years and had worked for private law firms, the California government, and DREDF. The idea of striking out on my own was intimidating, but I decided to see if I could work from home. I bought a desk (which I still have), used Word Perfect to print up some stationery and got some business cards.

DREDF generously allowed me to continue working on the Talking ATM cases, which grew into the first web accessibility cases, which set the course for the next twenty five years.

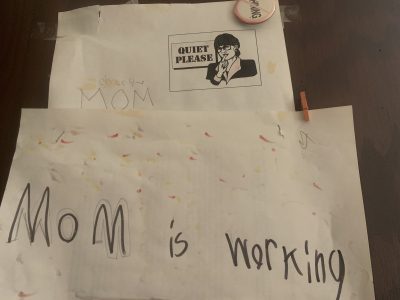

My daughters are grown and out of the house now, but the handwritten sign on the door to my office — which has been in that upstairs bedroom ever since — still remains. “Quiet Please,” it says, with a 90’s-style graphic of a woman with finger to lip. “Mom is Working.”

My daughters are grown and out of the house now, but the handwritten sign on the door to my office — which has been in that upstairs bedroom ever since — still remains. “Quiet Please,” it says, with a 90’s-style graphic of a woman with finger to lip. “Mom is Working.”

The “no whining” button peaks out from the top corner.

Back to topWhy LFLegal

When I hung my shingle (well, my “quiet” sign) in my upstairs bedroom, having a website was the furthest thing from my mind. Even though I helped negotiate the first web accessibility agreement in 2000, it wasn’t until 2008 that I realized I needed my own site.

I was going to use the url of LaineyFeingold [dot] [com]. But my friend and blind scientist / inventor Josh Miele set me straight. “No one will know how to spell Lainey,” he told me, “and no one will know how to spell Feingold.”

But maybe more important for me as a disability rights lawyer, Josh told me that

With LaineyFeingold [dot][com] your email address won’t fit on one line of braille on your business card.Josh Miele’s advice

Josh suggested LFLegal and I grabbed it. Two years later I used it for my Twitter handle. LFLegal became a brand.

I’m sure a consultant would have charged me to come up with LFLegal, but listening to Josh was a lot less expensive. Seriously, though, cost had nothing to do with it. I often share the story of the the birth of LFLegal because it underscores a fundamental aspect of the way I’ve practiced law for the past twenty-five years.

Listening to, and following the advice of, disabled friends and clients (often one in the same) who have generously shared their expertise, stories and life experiences with me has made the past twenty-five years possible.

In the series of 25th anniversary posts I plan to write throughout this year, I’ll share more about those learnings, friends, and clients. For now I just say thank you to everyone who has made LFLegal possible.