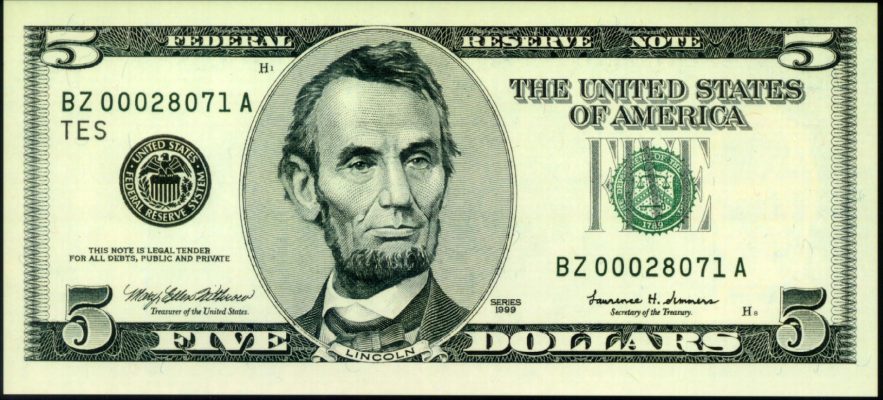

On Friday, October 3, 2008, U.S. District Court Judge James Robertson issued an historic injunction against the United States Treasury. In a case brought by the American Council of the Blind (ACB) and other blind advocates, Judge Robertson held that the Treasury “violated Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act by failing to provide meaningful access to United States currency for blind and other visually impaired persons.” The Treasury was ordered to take steps to make United States currency accessible to people who are blind. In his first ruling on this issue in 2006, Judge Robertson found that “of the more than 180 countries that issue paper currency, only the United States prints bills that are identical in size and color in all their denominations.” Washington, D.C. lawyer Jeff Lovitky handled the case for ACB. A copy of the Judge’s Order, and the Memorandum filed at the same time, is posted below.

Simplified Summary of this Document

ORDER AND JUDGMENT

The United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit having affirmed this Court’s Memorandum Order (Amended) of December 1, 2006 [72]:

- 1.

- IT IS ORDERED AND ADJUDGED that the defendant has violated Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act by failing to provide meaningful access to United States currency for blind and other visually impaired persons.

- 2.

- IT IS FURTHER ORDERED AND DECREED that defendant take such steps as may be required to provide meaningful access to United States currency for blind and other visually impaired persons, which steps shall be completed, in connection with each denomination of currency, not later than the date when a redesign of that denomination is next approved by the Secretary of the Treasury after the entry of this order and judgment.

- 3.

- This Order and Judgment does not apply to the one dollar ($1) note, and does not require the defendant to make any changes to the one dollar ($1) note. This Order and Judgment does not apply to changing the Series year or the signatures of the Secretary of the Treasury or the Treasurer of the United States on each note, nor to changing the machine-readable features on the notes that are not

visible to the naked eye. Notwithstanding paragraph 2 above, given that the defendant is currently engaged in implementing a redesign of the $100 note (”the NextGen $100″), the defendant need not comply with paragraph 2 above in connection with the NextGen $100 note until the date when another redesign of such denomination is next approved by the Secretary of the Treasury after the redesign that is currently in progress. - 4.

- The defendant shall file periodic status reports describing the steps taken to implement this Order and Judgment. The first such status report shall be filed no later than March 16, 2009, and each

succeeding report shall be filed every six months thereafter, until the defendant has fully complied with this Order and Judgment. - 5.

- The parties are directed to confer and attempt to reach agreement regarding plaintiffs’ claim for attorney’s fees and costs. If no agreement is reached, plaintiffs shall submit their application for

attorney’s fees and costs within 60 days of the date of this Order and Judgment.

JAMES ROBERTSON

United States District Judge

MEMORANDUM

In American Council of the Blind v. Paulson, 463 F. Supp. 2d 51 (D.D.C. 2006), I “declared that the Treasury Department’s failure to design, produce and issue paper currency that is readily distinguishable to blind and visually impaired individuals violates § 504 of the Rehabilitation Act.” Id. at 63. The Court of Appeals affirmed that ruling and remanded the case “for the district court to address the request for injunctive relief.” American Council of the Blind v. Paulson, 525 F.3d 1256, 1260 (D.C. Cir. 2008). The Treasury Department contends that injunctive relief is inappropriate and unnecessary: inappropriate because “courts should remand a case to an agency for decision of a matter that statutes place primarily in agency hands,” INS v. Orlando Ventura, 537 U.S. 12, 16-17 (2002), and unnecessary because the Department “has already begun the process of determining how to provide meaningful access [to currency] . . . [and] is committed to carrying this process to completion.” Dkt. 88, at 4-5.

Neither objection is compelling. Remand might be the appropriate remedy when an administrative decision is erroneous — as the Court held in Ventura — but not when the government has an established practice that violates the law. In such instances, in matters famous, see Brown v. Board of Educ., 349 U.S. 294, 300 (1955), and obscure, see Henrietta D. v. Bloomberg, 331 F.3d 261, 290 (2d Cir. 2003), district courts are free to issue an injunction demanding compliance with the law.1

And while I do not question the Treasury Department’s commitment to achieving compliance, the best-laid plans can be derailed by shifting priorities, limited resources, and the other vagaries of bureaucratic action. As I have noted, “[t]his Court has neither the expertise, nor, I believe, the power, to choose among the feasible alternatives, approve any specific design change, or otherwise to dictate to the Secretary of the Treasury how he can come into compliance with the law.” American Council of the Blind, 463 F. Supp. 2d at 62. But this Court does have the expertise and the authority to create goals and to hold the The Treasury Department also argues that an injunction would be inappropriate because it would the equivalent of mandamus, and mandamus is only permissible when a public official has violated a ministerial, rather than a discretional, duty.

See Dkt. 88, at 6. But that claim is based on language from the plaintiffs’ proposed order that is not in the Court’s injunction order. government to those goals. That is the purpose of this injunction.

The injunction order makes one significant change to the Treasury Department’s proposed order. See Dkt. 88, Ex. 2. I have not included paragraph four, which gave the Secretary carte blanche to delay the issuance of accessible currency if s/he determined that a redesign was needed to address a counterfeiting threat. Id. at ¶ 4. If the Secretary needs relief from the injunction for that reason (or any reason), s/he can file a specific request, properly supported.

I have also not included certain provisions that the plaintiffs requested. The plaintiffs are concerned that the proposed order would permit the Treasury Department to furnish the visually impaired with external note readers, rather than modifying the currency itself. See Dkt. 89, at 5-6. I am not prepared at this point, on this record, to foreclose such an option. Plaintiffs also seek a public comment period following the release of defendant’s semiannual status reports. The Department has agreed to a public comment period after the contractor has completed his study and before the Department chooses a course of action; that should suffice.

* * *

The injunction is granted by the order that accompanies this memorandum.

JAMES ROBERTSON

United States District Judge